On Donald Trump’s capricratic governance, marked by abrupt policy shifts, unpredictable actions, and decisions seemingly driven by personal whims rather than consistent principles or thorough analysis

Dec 20, 2024

Donald Trump’s presidency was a masterclass in governing by whim. His erratic decision-making, characterized by abrupt policy reversals, impulsive actions, and disregard for established norms, left both allies and adversaries bewildered. This style of governance, which I here term “capricracy,” undermined democratic principles and eroded public trust in the executive branch.

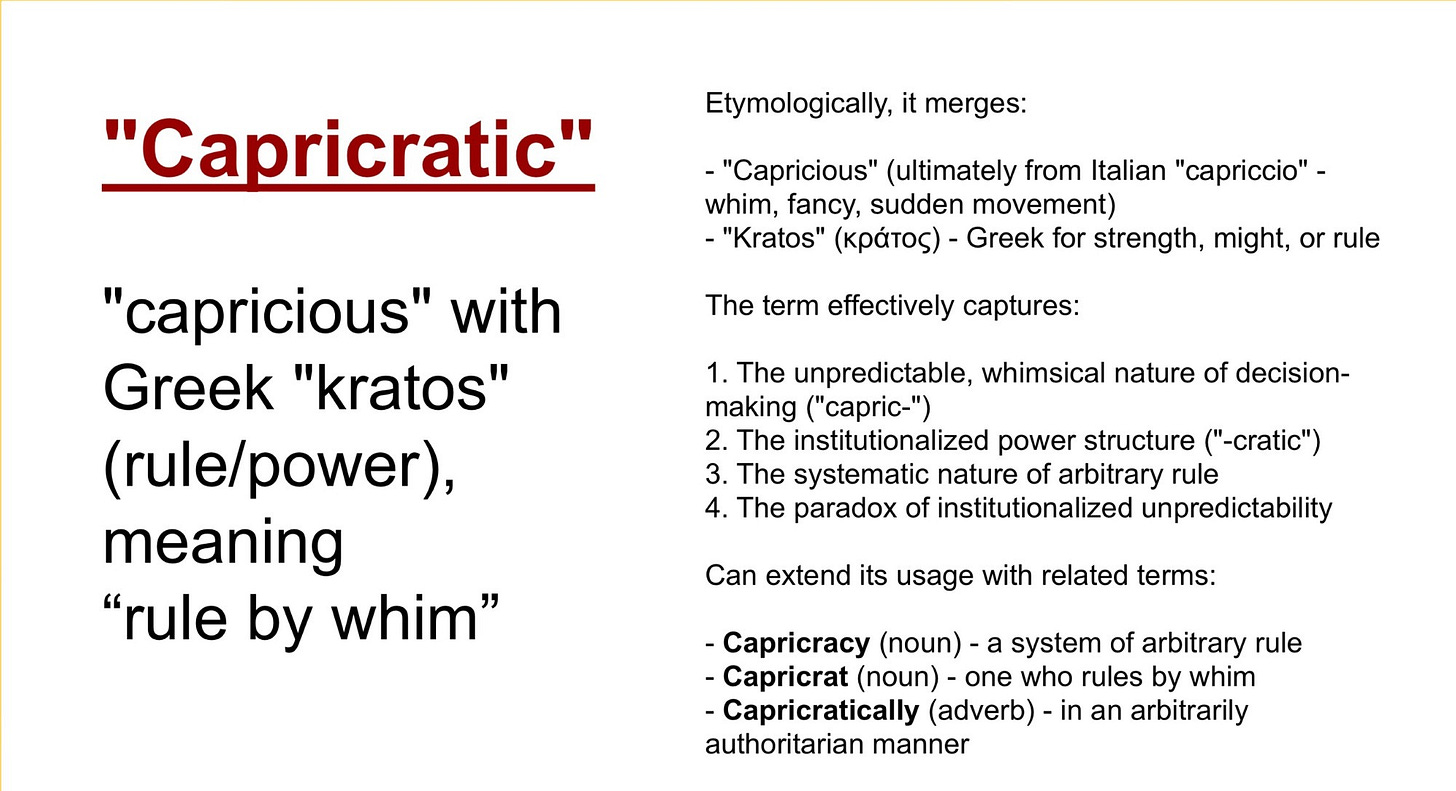

In the wake of Trump’s presidency, political analysts have struggled to categorize his distinctive style of governance that went beyond simple authoritarianism or populism. While terms like “authoritarian” or “strongman” capture aspects of his approach, they miss a crucial element: the deliberate wielding of whim as a tool of power. This phenomenon, which I’m calling “capricracy”—from the Latin “capricious” and Greek “kratos” (power)—represents a form of rule where unpredictability itself becomes a mechanism of control.

Key Point: While conventional autocrats typically build systematic mechanisms of control, the capicrat deliberately maintains institutional instability.

This is a brief post and intended to heuristically generate thought and discussion. I’m suggesting here that the concept of capricracy helps us understand how seemingly erratic leadership can serve strategic purposes. When Trump abruptly reversed course on family separation policy in 2018, shifting from “zero tolerance” to a hasty retreat within six weeks, it appeared simply impulsive. But viewed through the lens of capricratic governance, such reversals serve to keep both allies and opponents off-balance, making it difficult to mount organized resistance or even predict the next move.

Capricratic Governance

A hallmark of Trump’s capricracy was his penchant for sudden and unexpected policy shifts, often driven by special-interest pressures or personal pique. This unpredictability manifests in multiple ways. Consider Trump’s approach to foreign policy, where major diplomatic announcements often came via early morning tweets. His sudden declaration of a transgender military ban on Twitter blindsided military leadership and upended established policy-making processes. The attempted purchase of Greenland, proposed without diplomatic groundwork, similarly exemplified governance by whim rather than careful statecraft. At one point, TikTok was a threat, then it was supported.

More generally, the strategic value of this unpredictability becomes clearer when examining Trump’s handling of major policy initiatives. Perhaps we can consider a variety of statements and decisions:

● Abrupt Policy Reversals: Trump frequently reversed course on significant policies, often in response to public backlash or shifting political winds. Examples include the reversal of the family separation policy, the attempted rescission of DACA later deemed arbitrary and capricious by the Supreme Court, and the fluctuating stance on abortion policies. This created uncertainty and instability, making it difficult to predict or understand the administration’s direction.

● Impulsive and Unilateral Actions: Many of Trump’s decisions appeared impulsive and lacked thorough consideration or consultation with experts. His use of Twitter for major policy announcements, such as the transgender military ban, exemplified this impulsivity. The withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the imposition of tariffs on steel and aluminum imports were also criticized for their lack of strategic planning and potential negative economic consequences.

● Inconsistent and Contradictory Positions: Trump often exhibited contradictory positions on critical issues, leading to confusion and a perception of erratic decision-making. His fluctuating positions on vaping regulations, COVID-19 relief negotiations, and abortion demonstrate this inconsistency.

● Disregard for Established Norms and Processes: Trump frequently disregarded established norms and procedures, such as attempting to hold the G7 summit at his own resort, proposing the purchase of Greenland, and revoking security clearances for political opponents. These actions demonstrated a disregard for traditional diplomatic protocols and ethical considerations.

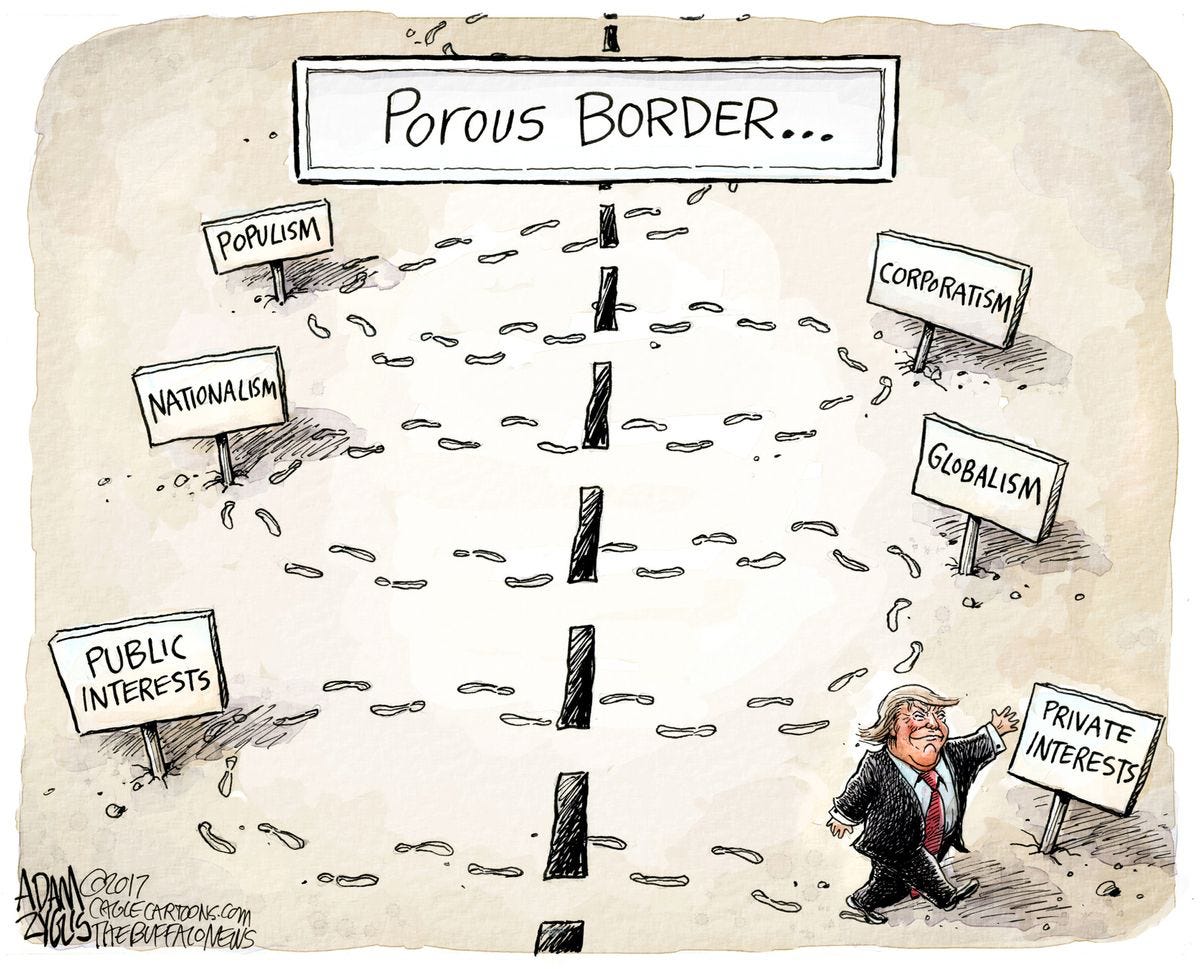

● Prioritizing Personal Interests and Political Gain: Several decisions, like the G7 summit at Doral, raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest and a prioritization of personal gain over public good. Appointing Elon Musk, a figure with extensive business interests, to a government efficiency panel further fueled these concerns.

● Use of Military Force for Domestic Issues: Trump’s threats to deploy military force to quell protests and for mass deportations raised significant concerns about the militarization of domestic issues and the potential for executive overreach.

Is this merely impulsive behavior? Such dramatic policy reversals served multiple purposes: they demonstrated the leader’s absolute power to change direction at will, exhausted opposition forces who struggled to respond to rapidly shifting positions, and created an atmosphere of continual uncertainty about what might come next. Whether consciously strategic or not, such decisions exemplify how capicratic governance bypasses traditional decision-making processes, keeping both allies and opponents perpetually off-balance.

Related Terms on Personal and Autocratic Rule

In this brief post, I do not suggest that I am entirely original in thinking about the dynamics represented in capricious governance.

For example, political scientist Rebecca Tapscott’s work on “institutionalized arbitrariness” helps illuminate how such apparently chaotic leadership can actually consolidate power. By creating an environment of constant uncertainty, where even basic policy positions might reverse overnight, capricratic leaders prevent opposition forces from coalescing effectively. Trump’s fluctuating positions on COVID-19 relief negotiations in 2020 exemplified this dynamic, as congressional leaders struggled to respond to positions that shifted dramatically from day to day.

The capricratic leader often leverages what scholar Xavier Márquez calls the “mobilization of charisma” – using personal appeal to bypass institutional constraints. Trump’s tendency to make major policy pronouncements at rallies, circumventing traditional channels, illustrates this approach. When he announced plans to impose steel and aluminum tariffs without the usual interagency review process, it demonstrated how personal whim could override established procedures.

Relatedly, and drawing on Max Weber, Xavier Márquez identifies three broad strategies individuals use to establish personal rule:

● Mobilization of Charisma: This strategy leverages emotional attachments between a leader and followers to broaden the reach of allegiance to the leader. This can involve undermining formal norms that limit power or introducing new norms that expand a leader’s discretion.

● Mobilization of Legality or Formal Authority: This involves using legal discourses and procedures to expand the scope of formal executive powers. This can include crafting persuasive arguments to justify changes to constitutions or laws that benefit the leader.

● Mobilization of Informal Authority: This strategy utilizes a leader’s position in a network of interests, often through patronage, to undermine other forms of authority. This can involve placing loyalists in positions of power within formal institutions.

These categories allow what at first may seem a mixture of processes and levels of analysis to be better integrated into a sense of agency for initiating and provoking a personalistic and capricratic form of power.

Capricrat in Chief: A Presidency Defined by Whim

In response to my suggestion of capricracy on Bluesky, McGill University’s Maria Popova suggested alternative terms like “whimocracy” and “whimocrat” to describe this phenomenon. After all, “capricracy” is, indeed, “a bit of a tongue twister.” Yet “capricracy” captures the systematic nature of what might otherwise appear as mere capriciousness. Trump’s pattern of abrupt policy shifts – from threatening military deployment against protesters to reversing environmental regulations – reveals how unpredictability itself becomes a tool of power.

Importantly, capicracy differs from simple authoritarianism. While traditional autocrats might build systematic mechanisms of control, the capricrat deliberately maintains an atmosphere of uncertainty. Trump’s approach to staffing key positions illuminates this distinction. Rather than building a stable power structure, he frequently left positions filled by “acting” appointees, creating a permanent state of temporary leadership that enhanced his personal authority.

The impact of capricratic governance extends beyond immediate policy outcomes. When Trump attempted to rescind DACA protection for young immigrants, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled the action “arbitrary and capricious” – a legal rebuke that ironically captures the essence of capicratic rule. Such governance undermines not just specific policies but the very concept of predictable, rule-based administration.

The corrosive effects of capricratic rule on democratic institutions become clear in examples like Trump’s handling of the G7 summit location. His initial insistence on hosting at his Doral resort, followed by a rapid reversal under pressure, demonstrated how personal whim could blur the lines between public office and private interest. Similarly, his appointment of business figures like Elon Musk to government efficiency panels showed how capricratic governance can bypass traditional concerns about conflicts of interest.

Understanding Trump’s presidency through the lens of capricracy offers insights beyond simple categorizations of authoritarian behavior. It helps explain how seemingly chaotic leadership can actually serve to concentrate power, as the leader’s unpredictability becomes a source of authority rather than a limitation. This framework may prove increasingly valuable as democratic nations grapple with leaders who leverage unpredictability as a political tool.

Essentially, unpredictability itself can function as a sophisticated political strategy. The challenge for democratic institutions lies in developing resilience against capricratic governance. Traditional checks and balances assume a certain predictability in executive action. Traditional democratic institutions, designed to operate through predictable processes and established norms, find themselves particularly vulnerable to leaders who weaponize uncertainty. When leaders deliberately cultivate unpredictability, new mechanisms may be needed to preserve democratic norms while responding to rapidly shifting policy positions.

As we continue to analyze Trump’s impact on American democracy, the concept of capricracy provides a lens that could become an even more valuable analytical tool as we will soon observe a string of official decisions made once he takes office. It may help us understand how governance by whim, far from being merely erratic, can serve as a sophisticated strategy for power consolidation. Recognizing this pattern is crucial for defending democratic institutions against leaders who transform the occurrence of unpredictability from a political weakness into a strategic weapon.

Gerardo Martí, Ph.D.

William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Sociology, Davidson College, Davidson North Carolina, founded 1837

Recent Comments